Story by Brigid O’Connell, Herald Sun

Photos by Jason Edwards, Herald Sun

Kira Gascoigne was born with her heart outside her body. But despite the odds being against her, she has survived one of the most complex heart surgeries performed in Australia.

The New Year means new life for baby Kira Gascoigne.

The 11-month-old has survived one of the most complex heart surgeries performed in Australia, to fix a quintuple of life-threatening cardiac and abdominal abnormalities – including being born with her heart outside her chest.

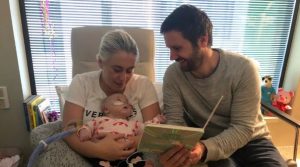

Now, Kira is preparing to celebrate her first birthday – a milestone her parents Chris and Kim Gascoigne were never confident she would make – in the same year that her saviour, the Royal Children’s Hospital, celebrates its own major milestone – 150 years.

“We are incredibly relieved that Kira finally got to come home with us,” Mr Gascoigne said.

“We are so grateful for all of the staff at the RCH for helping her get to this point.”

Kira Gascoigne, 11 months, was born with her heart outside her body. Picture: Jason Edwards

Kira had fought against the odds at every step of the way to arrive into the world.

Her conception was the result of multiple IVF rounds, and she was the one embryo to survive genetic testing.

But Kim and Chris’s joy was short-lived.

The 22-week scan revealed a rare and life-threatening problem with the plumbing of their baby’s heart; a defect potentially associated with multiple genetic issues, and requiring a series of open heart surgeries across an entire childhood.

The couple could feel their long-awaited baby moving at this point. They had a shortlist of names by this stage. They had already started daydreaming about the books they would read her, and the family adventures they would have.

The new diagnosis at the next scan was more reassuring; still a heart defect, but one that would require fewer surgeries and give them the first six precious months at home before surgeries started.

Kira Gascoigne was taken straight to the RCH after birth after the severity of her heart problems was found. Picture: Supplied.

When Kira was born via caesarean section on February 22 she was breathing on her own, but she worked overtime to take each breath.

New parents think to count the number of fingers and toes upon first inspection of their newborn. They would never think to check all the organs were inside the body.

Chris followed his daughter to the resuscitation station on the side of the room. He could see her little heart flapping under a piece of skin. He knew it didn’t look right. A buzzer was pressed and the delivery room filled with a dozen extra doctors and nurses.

Kira was sedated and whisked away, ready to be transported down the road to the Royal Children’s Hospital.

“We didn’t even know if she would survive the first night,” Mrs Gascoigne said.

“It happened so quickly, I didn’t feel like I had a baby.

“The paediatrician said it was life threatening, but they didn’t know what was going on and they’d take it one step at a time.”

Kira was diagnosed with pentalogy of Cantrell, a cluster of abnormalities which includes four different heart defects that collectively stop oxygen-rich blood being pumped around the body. She was missing a breast bone, and her heart sat outside her chest, covered by a thin membrane.

Kim and Chris Gascoigne get precious cuddles with newborn Kira, after the diagnosis of her heart conditions. Picture: Supplied.

Chris would relay the updates to his wife, still a maternity patient herself at another hospital and she would Google the finding, alone in her hospital bed, with heart-wrenching results. An internet search of “ectopic heart” will tell you 95 per cent of babies won’t survive.

But unbeknown to them, Kira was being cared for in a hospital that had performed the highest number of ectopic cardiac repairs in the world – all successfully.

Kira spent her first three months in the world living on the RCH’s Butterfly ward, where the priority was to keep her stable.

During this time Mrs Gascoigne would express breast milk every three hours through the night – a constant reminder of her baby who was not with her – and the couple returned to their daughter’s bedside by 7am.

They read Kira books and cuddled her the whole day, until they left at 8pm – a routine they repeated every day.

It meant a different series of “firsts” to what they had imagined. The first cuddle was with an intubated newborn; a plastic tube running down into her airways to help her breathe. The first walk was a stroll in the pram around the cardiac ward, attached to an oxygen tank and monitor.

Her first bath was at nine weeks of age.

“I felt like I couldn’t bond with her for such a long time, maybe even until we got home,” she said.

“I had all these plans for what this time with our baby would be, and now I was facing planning a funeral.

“There was never talk about what was ahead, it was only ever one day at a time.

“They never wanted to say too much because they couldn’t guarantee the outcome.”

Kira Gascoigne spent three months on the Butterfly ward at the RCH.

When Kira was three-months-old, cardiac surgeon Yves d’Udekem explained to Chris and Kim his life saving plan.

With paediatric surgeon Joe Crameri, they had successfully put the hearts of children back into their chests four times in the past six years.

“When people see the heart outside the chest, they rush in to put it back to make it look normal,” Prof d’Udekem said.

“What we’ve learnt is if we don’t rush in and we give time to the baby, you have more space in the chest and abdomen.

“If you don’t try to have a perfect result where you have the heart completely in the chest, you may achieve better results.”

Royal Children’s Hospital surgeons have successfully put Kira Gascoigne’s heart back inside her chest. Picture: Supplied.

They planned to go in when Kira was four months old; firstly fixing the plumbing problems and hole in the heart, and then placing the walnut-sized heart back inside the chest.

But within a week, and with Kira having episodes where she would turn blue, the operation was brought forward.

Again, the odds were against her. Once in the operating room, Prof d’Udekem and Mr Crameri found that her heart was not only outside the chest, it was rotated.

This blocked all access to the abnormal structures underneath they needed to fix and doubled the length of the surgery.

Kira Gascoigne, 11 months, is just learning how to eat and drink after her nasal gastric tube was removed. Picture: Jason Edwards

The complexity of the operation and the toll it took on her tiny heart, saw Kira placed on ECMO. The heart-lung bypass machine, reserved for the sickest patients in the hospital.

After three days, they started the staged procedure of closing her open chest, tightening little by little, over 10 days.

“The heart needs time to adapt to work in its new position,” Prof d’Udekem said.

“We take your heart and we sit on it, basically, plus the lungs as well.

“I was confident it would work, but there was a week of doubt after I closed the chest.

“Thankfully she turned the corner and started improving from there.”

And now, as she prepares to ring in the New Year, Kira continues to meet the next milestones.

She is sitting up by herself, has started finding her voice and waving. The nasal gastric tube she has relied on for all nutrition for the past 10 months has just been removed, allowing her to start eating and drinking for the first time.

“I always wanted a happy, healthy baby that I could have as my little best friend. Someone I could go shopping with and travel the world with,” she said.

“Now I just want her to have health and happiness and to not feel disadvantaged in life because of what’s happened to her.”